First Conference of the Project: Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC).

Published:

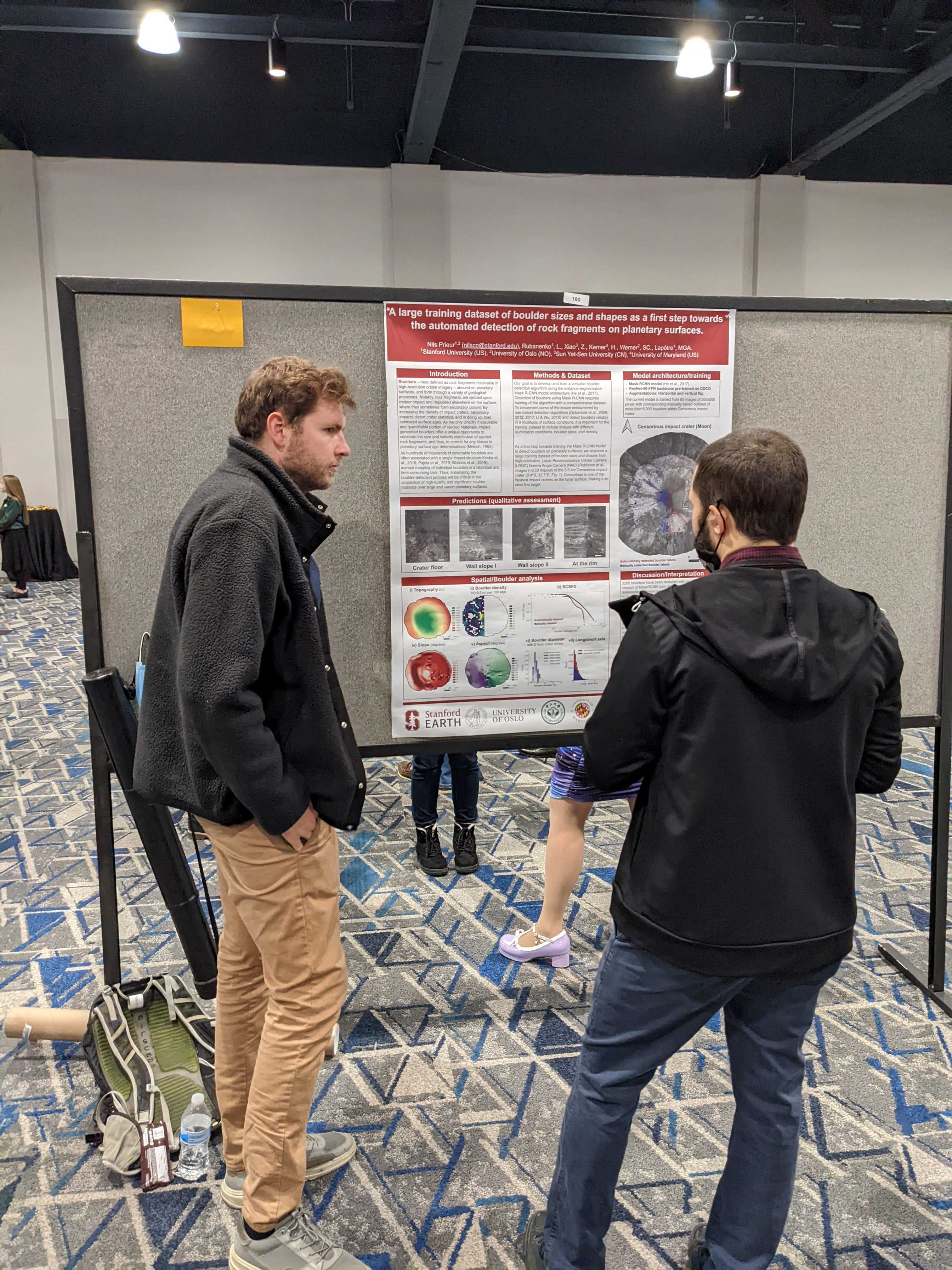

Hey everyone! Big milestone: I attended the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC)—the first conference of the BOULDERING project. The LPSC abstract deadline sneaks up early in January, and though my results were still in their infancy, I decided to go for it. My abstract, titled “A Large Training Dataset of Boulder Sizes and Shapes as a First Step Towards the Automated Detection of Rock Fragments on Planetary Surfaces,” focused on the data I’ve labeled so far, the challenges encountered, my plans, and how our method stacks up against existing approaches. It felt like the perfect way to introduce myself and the project to the planetary science community. A “Hello, I’m Nils, and this is BOULDERING” moment!

My abstract was accepted as a poster presentation—yay! My goal leading up to the conference was to train a reasonably robust version of the Mask R-CNN model, study its predictions, and include the results in my poster. Easier said than done! For those unfamiliar, most deep learning models (like Mask R-CNN) are originally trained on straightforward datasets—think photos of cats, cars, or human faces—not satellite images of boulders at the very edge of image resolution. This required a lot of customization, like tweaking the model’s parameters to suit planetary data.

The default parameters? Forget it. I had to dig into the Detectron2 documentation and adjust things like image scales, anchor sizes, and learning rates to handle small boulders effectively (here’s the config reference for those curious: Detectron2 Config). After a lot of trial and error, I trained the model using labeled data from the western side of the Censorinus crater. For testing, I made predictions on the eastern side—a region the model had never “seen.”

The results? Far from perfect! Many boulders were missed, but the model still managed to detect some. Importantly, it hinted at areas where I needed more labeled examples. For instance, if the model consistently failed to detect boulders with certain characteristics, it essentially “asked” for more examples of that type. This feedback loop—using predictions to improve the training dataset—was a promising first step.

The conference itself was fantastic. The planetary science community is incredibly supportive, and I received great feedback on the project. I also connected with researchers using deep learning for entirely different applications, which was a goldmine for inspiration. Seeing how others approach their challenges made me think of new ways to tackle mine.

All in all, a productive, inspiring, and fun experience. The BOULDERING project is officially on the map! Looking forward to implementing some of the lessons learned and improving those predictions. Until next time—take care! 😊

Caption: Let’s the conference begins, Woodlands, Texas (US).

Caption: Let’s the conference begins, Woodlands, Texas (US).

Caption: Presenting my preliminary results with a poster. Lot of people stopped by and were interested. Niceuru :)

Caption: Presenting my preliminary results with a poster. Lot of people stopped by and were interested. Niceuru :)

Caption: Picture of Lior’s presentation (who is another postdoc in the group). He is working on a similar topic, but focusing on deep-learning for the detection of dunes on Mars.

Caption: Picture of Lior’s presentation (who is another postdoc in the group). He is working on a similar topic, but focusing on deep-learning for the detection of dunes on Mars.